Limited Time Discount! Shop NOW!

In the mud of Zurich Alan Smith risked it all and won the game. While his teammates celebrated Ian Harte’s equalising free-kick, Smith stayed in the penalty area to fight Grasshopper after Grasshopper; the referee felt tested, but let him carry on, and a winning goal wasn’t far behind. It was the striker’s second goal in a season ruined so far by injury. He was taking his chance to play alongside Robbie Keane while Mark Viduka was away with Australia.

“Alan worked very hard, and although I was pleased with his work rate, he needs to control his fiery attitude,” said Leeds’ manager David O’Leary. “There were times when he didn’t need to get involved in things, when he could have just walked away, so he still needs to learn, and he will. It will take time, but he is improving.”

O’Leary was happy to live with the aggression if it meant goals, because that could mean the Premiership title for Leeds. After a year with Rio Ferdinand at the back, Leeds had the best defence in the top flight. So far in 2001/02 they’d conceded seven goals in twelve games, and only one at home, where United’s unbeaten run was now eighteen games. At Elland Road at the weekend they had a chance, against Aston Villa, to go top of the league above Liverpool; but then, so did Villa if they won. Leeds would be far ahead of them both if only their goals scored matched goals against: the defence was the best in the league, but the attack had only scored fifteen, one more than last placed Ipswich Town.

Smith had his own aim in mind. “It’s my dream to go to the World Cup but the competition is tough,” he said, listing Michael Owen, Emile Heskey, Robbie Fowler, Andy Cole, Kevin Phillips, Marcus Stewart and Teddy Sheringham as contenders for Sven Goran Eriksson’s attention. After his ankle injury, though, Eriksson had brought Smith straight into the squad. “If I reach the end of the season knowing I couldn’t have done more, yet I still haven’t made the squad, then fair enough,” Smith said, “But I’ll definitely be upset if there’s a single doubt in my mind that I could have done better.”

That thought inevitably brought other minds back to his disciplinary record: three red cards in 87 games for Leeds, plus another for England U21s. Like O’Leary, Eriksson seemed to think the temper was worth persisting with, but no squad could carry a risk of suspension into a World Cup. England had to be sure that if Smith went with them to Japan and South Korea, he’d behave and be able to play.

Smith didn’t think that would be a problem.

“Leeds mean so much to me. Because of that, I probably go over the top at times. But everyone who knows me says it only happens when we are getting beaten. I don’t like losing no matter what I play.”

Which made his actions in the game against Villa even more perplexing. Leeds were drawing in the first quarter of an hour when Smith took his first two swipes at Villa defender Alpay, either of which could have earned a booking from Neale Barry, the referee. As in Zurich, Smith was let off, and scored soon after, channeling his hunger for combat by chasing Alan Wright into the corner and forcing him into a panicked backpass. The ball went to Robbie Keane who, with goalkeeper Peter Schmeichel stranded, gave it to Smith; from a tight angle he smacked the ball into the net, sending Steve Stone in with it for good measure.

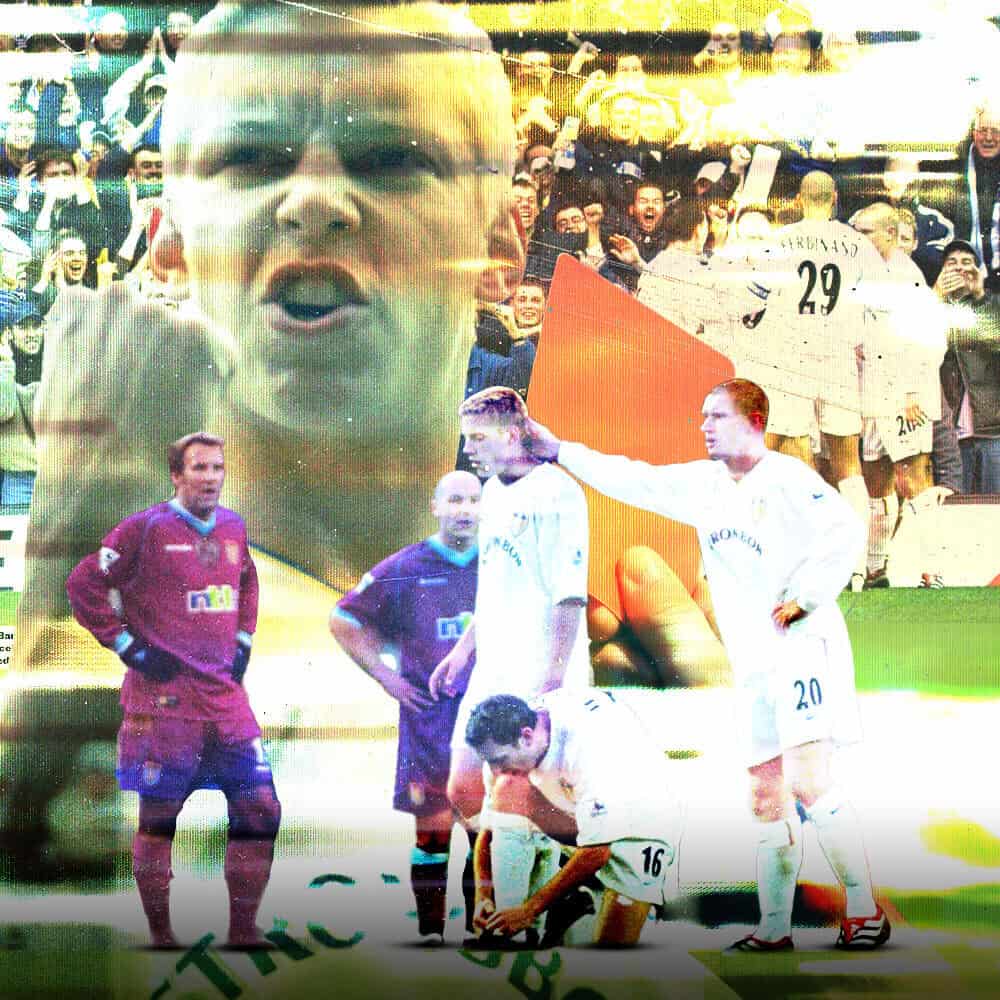

It was Smith all over: winding up opponents, getting them worried, seizing on their mistakes. But what followed fifteen minutes later was all about Smith, too. His team had the lead and, with their defence, every expectation of winning the game, but in an innocuous tussle with Alpay, Smith couldn’t resist another nudge. Off the ball, he aimed an elbow into his ribs — “but I don’t think he chose which part of his anatomy to hit,” observed Villa boss John Gregory. Alpay went down, the red card went up, Smith went off, telling Gregory and the lipreading viewers at home that Alpay was a “cheating, diving twat.”

Leeds were almost down to nine within two minutes, when debutant Seth Johnson’s only saving grace was that his scything tackle was so late Stone had plenty of time to evade him. The referee settled for a yellow, adding to Johnson’s four that season for Derby and meaning suspension, while from the free-kick Paul Merson hung a cross to Nigel Martyn’s back post and Hassan Kachloul equalised with an excellent volley.

As if emboldened by Smith’s red card, instead of chastened, the players spent the rest of the game testing Neale Barry’s control of it, and he failed miserably. Early in the second half, when Ian Harte crossed a free-kick, Eirik Bakke stayed down injured in the penalty area, and Villa took the chance to counter attack. While Leeds’ players pointed for the ball to go out, Danny Mills forced Lee Hendrie into giving it up, then forced him to hear his views on the subject; Hendrie put his hand on Mills’ face and shoved. In a pub it would have been the start of something, and Mills looked ready to swing, until he remembered this was a football pitch, and the best way forward was down. Putting his hand to his face he crumpled into a heap, waiting on the floor until Hendrie was told to march.

The orders never came. After consulting the linesman, Barry only showed Hendrie a yellow card, leaving it to John Gregory to impose discipline. He’d already given his player a piece of his mind while expecting a red card; now he subbed him off and sent him down the tunnel himself, promising a club fine. “You can call it bold or stupid,” said Gregory, perhaps polishing his own ego by claiming he’d sacrificed a potential matchwinner for the greater good. “I sent him to the dressing-room to underline how I felt.” Hendrie didn’t agree. “It’s pathetic that Mills tried to get another player sent off, a fellow professional — it was unbelievable,” he said. “But Mills has got a reputation for it and I don’t agree with the way he has gone about things.”

O’Leary, after watching Keane miss a one-on-one chance with Schmeichel bearing down on him, and Ferdinand heading against the post with the keeper stood still, declined to make any pointed observations. Alex Ferguson, unhappy with media coverage of what was expected to be his final season in charge at Old Trafford, had just announced he was no longer speaking to the press; O’Leary didn’t go that far, but was similarly inspired into silence by the way his words had been construed after incidents earlier in the season.

“I’m not discussing it,” he said, cutting off Peter Drury’s post-match question. “Sorry. I’ll let you discuss it. You don’t get into trouble, I do with what I say. And I’d be embarrassed if I had to say what I needed to say today.”

So instead the papers turned back to Smith’s self-assessment earlier in the week: “The gaffer and the rest of the staff have tried to control me and I am learning from what they say. But there are occasions when I can’t stay on the right side. Sometimes you overflow.”

And to O’Leary’s pre-game comments about how Smith had to learn to walk away, and about what he wanted from his strikers.

“It is up to Alan and Robbie to keep Mark Viduka out when he comes back, although I’d hate to put the pressure on them by saying they’ve two more games,” he had said. “But possession of the shirt is important and that’s how it will always be here” — possession Smith was squandering with his latest three-match suspension. O’Leary wanted more firepower — “My dream is to have two strikers on the bench and two playing because then we will be able to influence a game,” he said — but with Michael Bridges injured, Viduka and Harry Kewell away with Australia, and Smith suspended, he was down to one.

Meanwhile, in the day’s other big game, Liverpool beat Sunderland 1-0 thanks to a goal from Emile Heskey, putting them two points clear of Leeds with a game in hand. Gary McAllister had replaced Robbie Fowler at half-time, and there were rumours that the Reds’ striker might soon be on the move. ⬢

£16.00

£9.00

Copyright © The Square Ball Media Limited All Rights Reserved

WordPress Development By Clio Websites