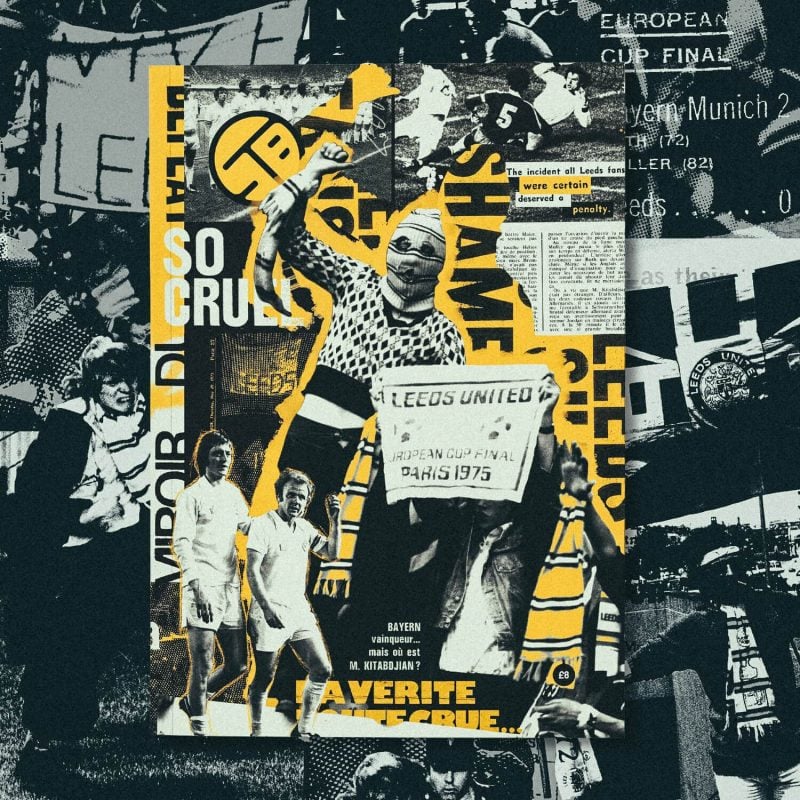

A Critic of Leeds

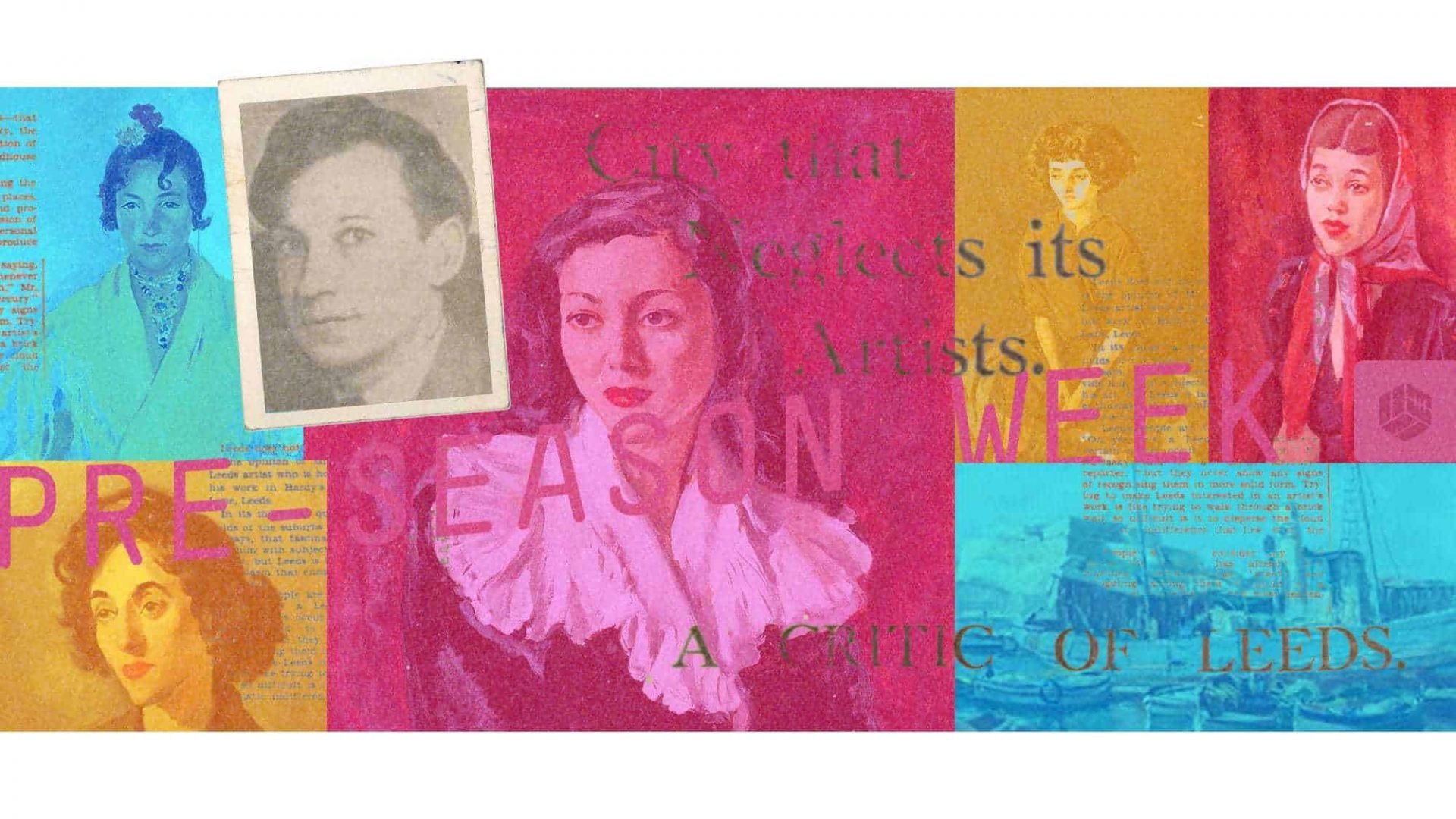

Trying to Walk Through a Brick Wall: Philip Naviasky Making Art in Leeds

Until I read about his studio burning down in a heatwave in July 1948, on the same day as Leeds United’s players came back for pre-season training, I hadn’t heard of Philip Naviasky. But now I’ve looked at his pictures and I like them, and I’ve found out that in 1928 he painted one of Alf Masser, the Alderman who got United together in October 1919 when Leeds City was shut down. So that’s two reasons and plenty enough to write a blog about him for The Square Ball’s Pre-Season Week.

Plus he became notorious in the 1930s for slagging off his home city even as he devoted his life to it, an important recurring theme for Leeds and its football club.

Naviasky was Leeds born to Polish immigrants, and a prodigy, winning a scholarship to Leeds School of Art aged thirteen, before passing a five-week entrance exam and becoming the youngest student ever admitted to London’s Royal Academy school, at eighteen, in 1913. There he produced one of his best known paintings, Portrait of a Rabbi. His friend and more famous contemporary Jacob Kramer was at Slade school around the same time, and by 1923 the Yorkshire Evening Post was claiming the Leeds School of Art was ‘probably’ getting more scholarships in London than ‘any other municipal school’. Despite that, ‘the city is not conspicuous in the eye of the art loving public as the home of many notable artists’. In other words, the YEP was having a habitual moan about people outside Leeds not giving the city credit for being the best at art.

By 1932, Naviasky had a few things to say about that, and as if to prove his point his comments gained his biggest headline and clearest photograph yet in the Leeds Mercury. ‘A Critic of Leeds’, the paper announced, with ‘Mr Philip Naviasky’ written boldly beneath his mugshot.

“Leeds people are very fond of saying, ‘Oh yes, he’s a Leeds artist,’ whenever certain names occur in conversation,” Naviasky was saying. “But they never show any signs of recognising them in more solid form.”

He had a ready example in Phil May, the Victorian caricaturist whose line-drawn cartoons were a major influence on 20th century illustration. In 2021 the Thoresby Society describe him as ‘loved and celebrated, not least in his home town of Leeds’, but Naviasky saw things differently in 1932.

“Everybody pays lip service to Philip May now, but he had to live and do his work in London, unrecognised in Leeds until he was dead. Now all Leeds acclaims him as a master.”

What about artists like our Naviasky, very much alive?

“Trying to make Leeds interested in an artist’s work is like trying to walk through a brick wall, so difficult is it to disperse the cloud of artistic indifference that lies over the city.”

Loining indifference is a consistent theme of local and Leeds United history, from Alf Masser’s quixotic attempts to drum up paying shareholders to support Leeds City, to United chairman Major Albert Braithwaite labelling the ‘lackadaisical’ populace that wasn’t getting behind its football club in the 1920s, to Don Revie lamenting empty spaces on the Elland Road terraces during the glory years.

The coverage given to Naviasky is typical: Leeds newspapers fuming that know-it-alls down in that London don’t recognise Leeds for all its wonders, but giving the most column inches to one of the best artists in the city only after he dared to criticise his home town.

And if you don’t think his comments cut deep, wait until 1938, when he returned to live in Leeds after marrying local tailoress, rabbi’s daughter and artist, Miss Millicent Astrinsky, and taking a two year painting tour of Europe. ‘I went to see Mr Naviasky to ask a difficult question,’ wrote the YEP journalist who welcomed him home. ‘I want to know why he had come back.’ Oh-ho, look what the cat’s dragged in! It’s himself then, is it? And just what makes you think you can come crawling back here?

The writer had even kept receipts, slapping the incriminating press cuttings from six years before down on the artist’s table. Naviasky ‘smiled a little smile, and knew he was dealing with a cunning sort of fellow.’

Naviasky said he’d come back for all the same reasons he’d given in praise of Leeds, alongside the criticism, back in ’32. He always maintained it was a beautiful place. “Yorkshire is a very paintable place and in Leeds itself are some fine river scenes. There are some fascinating industrial subjects for painting, too … For skies and clarity of the air since I’ve been back, Leeds has won.”

Showing the proper Yorkshire stubbornness, he hadn’t changed his mind about the city’s faults, but was prepared to admit Leeds wasn’t the only place with a problem. “I can’t say that since I’ve been back I’ve seen any great enthusiasm for art,” he said, “But I’m not blaming Leeds, it’s the same all over England.” Interest in art was dwindling, and with it, people’s chance to make their mark as individuals. New houses were being built without picture rails as standard, and now every house looked the same, part of a new fashion for “a mass man”. In Victorian times families had gone to galleries and bought a picture every year. Now husbands no longer asked, ‘What picture shall we buy this year, dear?’ but, ‘What car shall we have this year, dear?’ It was all, according to Naviasky, “modern silliness”.

A Leeds Mercury reporter took up the theme a few days later, going to interview Miss Barbara Heaton, owner of a gallery in Woodhouse Lane, who a year earlier had ‘given up a good secretarial job to take up the work of making Leeds art conscious’. The story ran on the women’s interest page beneath ‘Joyce Mather’s Shopping Notes’ (“Whitewood tea trolleys seem a worth-while investment”), hence the headline ‘Girl Runs Art Gallery’ and the news that Miss Heaton is ‘well under thirty, almost red-haired, very good to look at and lively to talk to’. If you didn’t like the paintings, at least you could gawp at the proprietress. The gallery’s show that month was of paintings Naviasky had done in Marseille, and Heaton wasn’t going to let other people’s lack of enthusiasm dim her own. She thought Leeds people were appreciative of art, deep down. They were just suspicious. ‘They are difficult to get into the gallery, and can hardly believe there is not a catch in it somewhere, this invitation to look at pictures without being asked to buy one.’

That was a finger on the problem Naviasky was trying to describe. For years he had been trying to release fine art from the perceived grip of monied elites, to share it with people who assumed that to look at art was as bad as a contract to buy, that the prices quoted for masterpieces meant they could never afford original art of their own. ‘Mr Naviasky wants the public to stop thinking of artists as curiosities,’ the YEP recorded. Inspired by his visits to the south of France, he wanted to find a way of replicating cheap kerbside art markets in Leeds, “despite the climate”, to make modern art shops as informal and welcoming as Barbara Heaton’s. He’d been pushing these ideas as early as 1929, exhibiting three paintings a month in the lobby of London’s Piccadilly Hotel, showing them to crowds who would never venture into the local fine art galleries.

Explaining himself to that cunning hack in 1938, Naviasky said he wanted artists to be ‘used more by the public … to decorate schools, shops, cafes and homes.’ Education committees should buy up paintings and display them in schools to inspire the pupils: ‘we might soon have an art-conscious generation’. And council art committees, who put on annual exhibitions of contemporary art, should commit to buying some of the paintings they show.

Googling Philip Naviasky now brings up a hefty list of works sold at auction; as well as teaching at Leeds College of Art, he was prolific until failing sight halted him in the 1960s. He died in 1983, Millicent in 1994. A painting of the beach at Hastings leads the valuation way, selling at £13,750 in 2008, five times the next-best, a portrait of Mrs Julie Lynn selling for £3,000 in 2013. Most of his paintings sell for considerably less than a car. This March, Tennants Auctioneers set a new record price for work by Phillip and Millie’s artist daughter, Sonia, £480 buying ‘Still Life with blue glazed jug and flowers‘. More significant than the prices, though, is a phrase repeating through the capsule biographies of Philip Naviasky: ‘Only recently gaining the deserved recognition … Naviasky’s decision to work in Yorkshire is perhaps responsible for his slow emergence to the rank of greatness.’ ◉

(This post is part of TSB’s Pre-Season Week 2021. Click here to read more pre-season stories)