Limited Time Discount! Shop NOW!

The sunshine of early autumn 1993 felt like a sign that Leeds United’s title hangover was lifting. The cobwebs that trapped the champions and almost dragged them down from the first season of the Premier League were being blown away.

At first in 1993/94 it didn’t feel like much had changed. Leeds drew away to Manchester City then beat West Ham at Elland Road, but three straight defeats, 4-0 at home to Norwich, 2-1 at Arsenal and 2-0 at Liverpool, plunged fans into familiar gloom. Then came changes. Mark Beeney took over from John Lukic in goal, and Leeds beat Oldham 1-0 at Elland Road.

A 2-0 victory over Southampton was even more significant. The match was won at The Dell, Southampton’s cramped stadium, where the end stands formed sharp diagonals with the roads behind them. It was the first time Leeds had won a league game outside Elland Road since 26th April 1992, the day they beat Sheffield United at Bramall Lane and won it.

It was hard to say what had changed since then. The backpass rule was one factor, but that changed for everybody. At Leeds it coincided with Mel Sterland’s absence and ultimately retirement through injury, leaving an unexpected gap at right-back that would have been easier to fill if Howard Wilkinson hadn’t spent £2m on David Rocastle to fill for Gordon Strachan. Strachan recovered from his back problems and Rocastle scored four in nineteen for the reserves. Sterland didn’t recover from his ankle problems and none of his umpteen replacements worked.

Some felt Leeds had become too old and too stale, and nineteen-year-old Gary Kelly’s summer elevation as Sterland’s heir was a rejuvenating jump to youth. Chris Whyte and Lee Chapman were moved on, but the defender’s replacement was David O’Leary, an even older player who quickly succumbed to injury, forcing 22-year-old David Wetherall to step in. Up front Brian Deane was bought for a club record fee from Sheffield United, but apart from Beeney and some of the FA Youth Cup winners on the bench, Leeds had a familiar, 1992 look about them.

That meant a midfield that would still be regarded as the Premier League’s best if it wasn’t for preconceptions about Gordon Strachan’s age. At 36 he couldn’t possibly keep it up for another season, could he? In the Sunday papers, Rocastle was trying desperately to avoid sounding like he was urging time to do its worst, but against Sheffield United at Elland Road on Saturday, Leeds had started the game as if their midfield quartet were going to disappoint Rocastle forever.

From right-back, Strachan sent a high pass into Sheffield’s half that was cushion-headed down by Rod Wallace, into the centre circle for Gary McAllister. With Deane and Gary Speed making runs either side, McAllister swerved upfield, and with former teammate Chris Kamara trying to block his way at the edge of the area, he shaped to pass out wide. Instead, he aimed for Alan Kelly’s near top corner. The powerful shot caught the keeper by surprise, and Leeds were ahead. The game was only five minutes old, and with McAllister to the fore, Leeds were threatening goals before and after.

There was only one problem, and it was Sheffield United’s away kit. “On the team strip sheet, the strip was listed as blue, blue, blue,” the referee, Philip Don, said later. “But of course there are many shades of blue.” And the shade Sheffield were wearing — cobalt blue, with a green sash — matched the referees’ outfits, right down to the socks. After ten minutes the players eventually gave up and asked the officials to change, which they did, into Leeds’ spare training kit. “I thought that they would be gone for twenty minutes, having to change socks and shorts as well,” said Wilkinson, sounding impressed at their quick change, although he can’t have been pleased with the loss of momentum it caused.

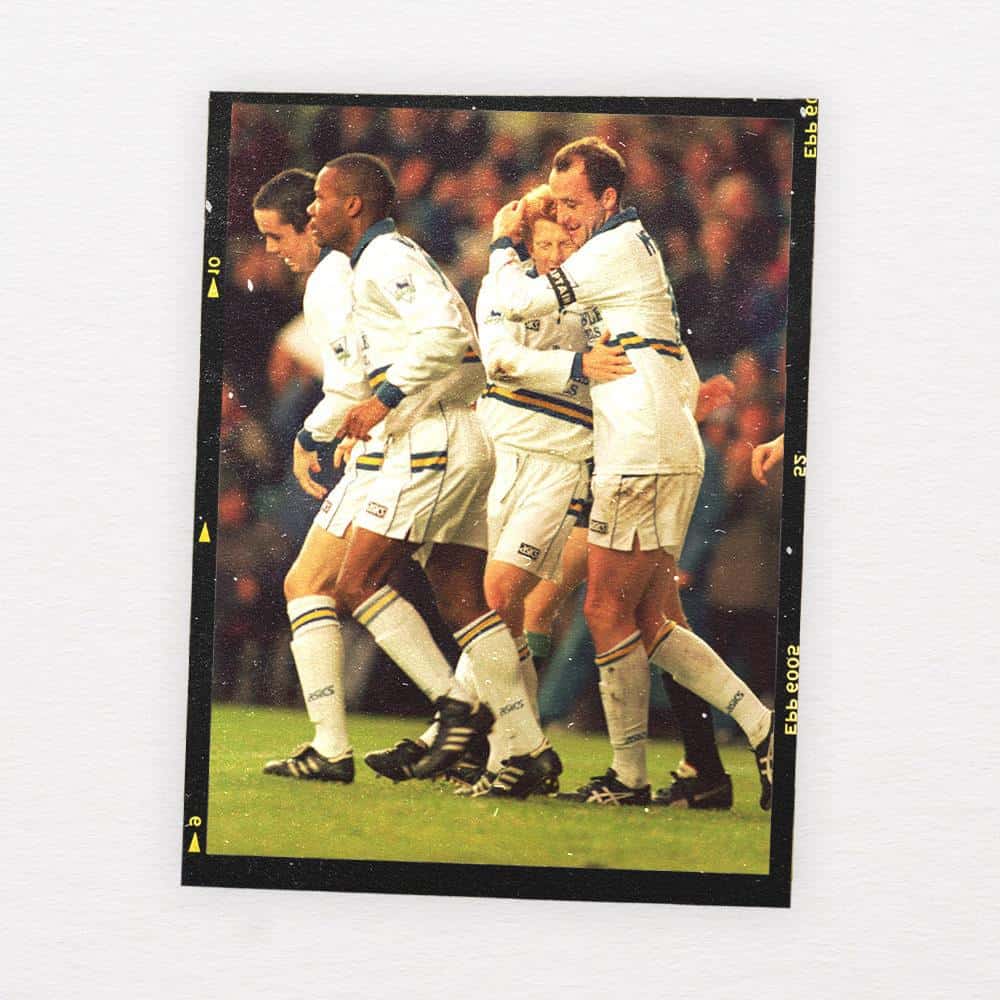

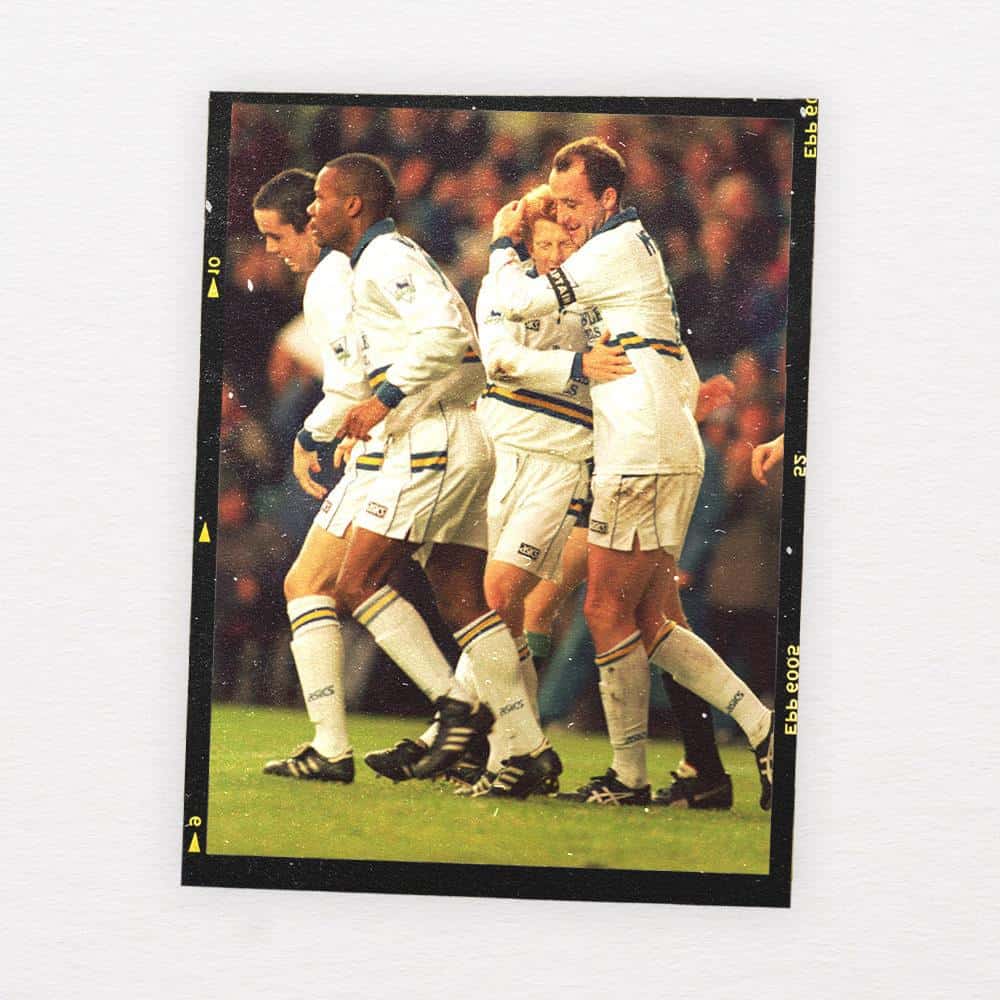

Leeds weren’t held up for long. With half an hour played, Beeney’s clearance went to the right wing, where Deane headed it inside towards the penalty area. Strachan darted into the channel and clipped the ball back over his shoulder, wrong-footing the defenders and giving him time to think about his next move with the bouncing ball. A shot would be with his own wrong foot, and he was doubtful, but nothing ventured, nothing gained, and his snapshot came with the element of surprise. A half-hit half-volley bounced past Kelly, surprised again, low at his near post. As everyone ran to congratulate him, he waved his left foot in the air, pointing at it and laughing, then covering his mouth as if in shock.

Leeds were relentless. Strachan’s cross was headed over by Speed; Strachan’s flick to Speed was crossed but Deane couldn’t connect cleanly to finish; Gary Kelly ran from right-back and tried shooting, one that Alan Kelly could save; David Batty and Strachan put Deane through the offside trap but his first touch took him too wide and his shot went over. He still hadn’t scored at Elland Road since his big move.

The only hitch was in defence, where in time added to the first half for costume changes, both sides stood and watched as Carl Bradshaw’s long throw bounced through the penalty area towards Beeney’s back post. Gary Kelly thought he’d better do something, but heading into his own net hadn’t been the plan.

In the second half only one team had the quality for the win. Batty chipped a disguised through ball for Wallace, who drew a good close-range save from Alan Kelly; Gary Kelly set off on another run from full-back and shot wide this time. But Dave Bassett had reminded his players that this was a Yorkshire derby and told them the first half wasn’t good enough, and their new application was exemplified by four minutes towards the end: Wallace and Mitch Ward were both booked for fighting, then Deane for what the Sunday Times called a ‘hideous’ foul on Tom Cowan, John Pemberton for a ‘crass’ tackle on Wallace and Glyn Hodges for elbowing Tony Dorigo. It was all Sheffield United had to offer. “If I had ten subs I would have tried to use them all,” said Bassett.

Their opponents might have been poor but it felt for Leeds like the more things changed, the more things might stay the same, or at least go back to how they were. Beeney for Lukic, Wetherall for Whyte, Kelly for Sterland and Deane for Chapman. After a year of toil in 1992/93, and finally making adjustments for age and injuries, Leeds could once again concentrate on getting the best out of that midfield.

But the kit clash hadn’t been the only problem. During the game, Batty could be seen holding his right arm by his side. Celebrating the first goal, he’d put his left arm around McAllister’s shoulder, keeping the right out of the way; someone tapped his right hand in celebrations of the second, and he pulled it sharply away. He got through to full-time without letting on what had happened: messing about in the warm up before the game, he’d tried to be goalkeeper for a McAllister shot, earning himself one cracker off the wrist and enough pain to miss the match. He knew what Wilkinson would say about that, so kept quiet and played, but after a night on the town with his wife when every well-wishing handshake was agony, Batty had no choice on Sunday morning but calling physio Alan Sutton. His x-ray diagnosed two broken bones in his hand. Batty was out of the next four games, only returning in late October, as a substitute, against Blackburn. ◉

(Every magazine online, every podcast ad-free. Click here to find out how to support us with TSB+)£3.00

£15.00

£15.00

£10.00

£15.00 Original price was: £15.00.£10.00Current price is: £10.00.