Limited Time Discount! Shop NOW!

‘This has been the year when Leeds United grew again into a very big club in our land,’ noted The Sunday Times after Howard Wilkinson’s side ended 1990 with a 3-0 win over Wimbledon at Elland Road. After the best part of a decade in the wilderness, Leeds were back in the First Division and had quickly proved they weren’t just there to make up the numbers. In fact, they were only getting better.

Leeds ended the year fourteen games unbeaten. Wilkinson was the reigning Manager of the Month. Lee Chapman couldn’t stop scoring. Gordon Strachan was hailing John Lukic as the best goalkeeper in England, and Wilkinson had his own unique way of agreeing. “He does have this knack, in his very lazy way, of being where the ball is.”

Suddenly it didn’t feel outrageous to suggest United had a team to rival the icons of Don Revie’s Super Leeds. And it was all thanks to the midfield. ‘Southampton could hardly have come under more pressure if it had been Giles and Bremner pulling the strings and Jones, Clarke, Lorimer and Gray bearing down on them,’ Peter Ball wrote in The Times after a 2-1 win at Elland Road at the start of December.

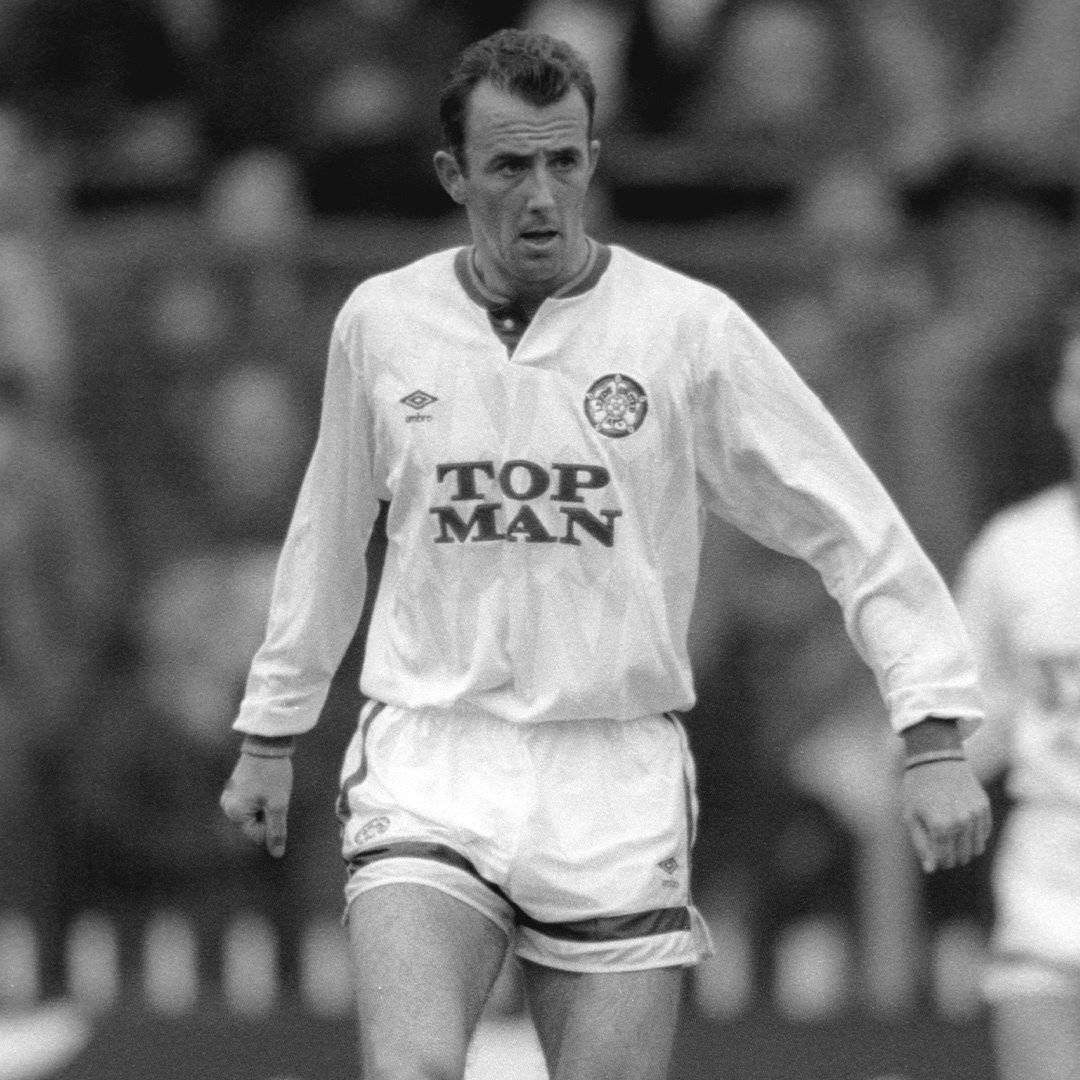

Johnny Giles and Billy Bremner’s names were never far from being mentioned whenever anyone witnessed the tenacity of David Batty. “I call him Billy Giles,” said his captain, Gordon Strachan. “He’s a weird character. In training, he’s terrible. He mucks about. Once the game starts, though, he’s buzzing everywhere — he can pass, tackle and head. When he starts scoring, he’ll be even better. He’s lucky enough to have all these qualities. Whether he uses them properly is up to him.”

Strachan was doing all he could to set an example for Batty to follow. Halfway through the season, he was considered the leading contender to win the Footballer of the Year award, and was soon rewarded with a new two-year contract that would take him up to the age of 36. Wilkinson had no concerns about any creaking limbs. There was no question of, “How does he keep on doing it?” It was only, “Why shouldn’t he keep on doing it?”

“His signing was one of the best pieces of business I have ever done as a football manager,” Wilkinson said. “I bless the day the deal went through.” Strachan was equally thankful he’d shunned a move to Lens to join Leeds. “I decided that I needed a camaraderie of people around me. I think you have to be a special type of person to go abroad, single-minded like Archibald and Souness. I need a laugh and a joke to keep me going. I’d be scared. Soon as you get there and take your trousers off somebody might start laughing and you can’t understand why.” He had no plans of slowing down and easing himself towards retirement, either. “I’ve not changed my style, which is reassuring. Somebody once said that when you get to thirty you’ll be able to play inside and have a couple of young boys running up and down the wing for you. I thought that sounded nice. But I get more enjoyment coming off a park as a winner and feeling shattered.”

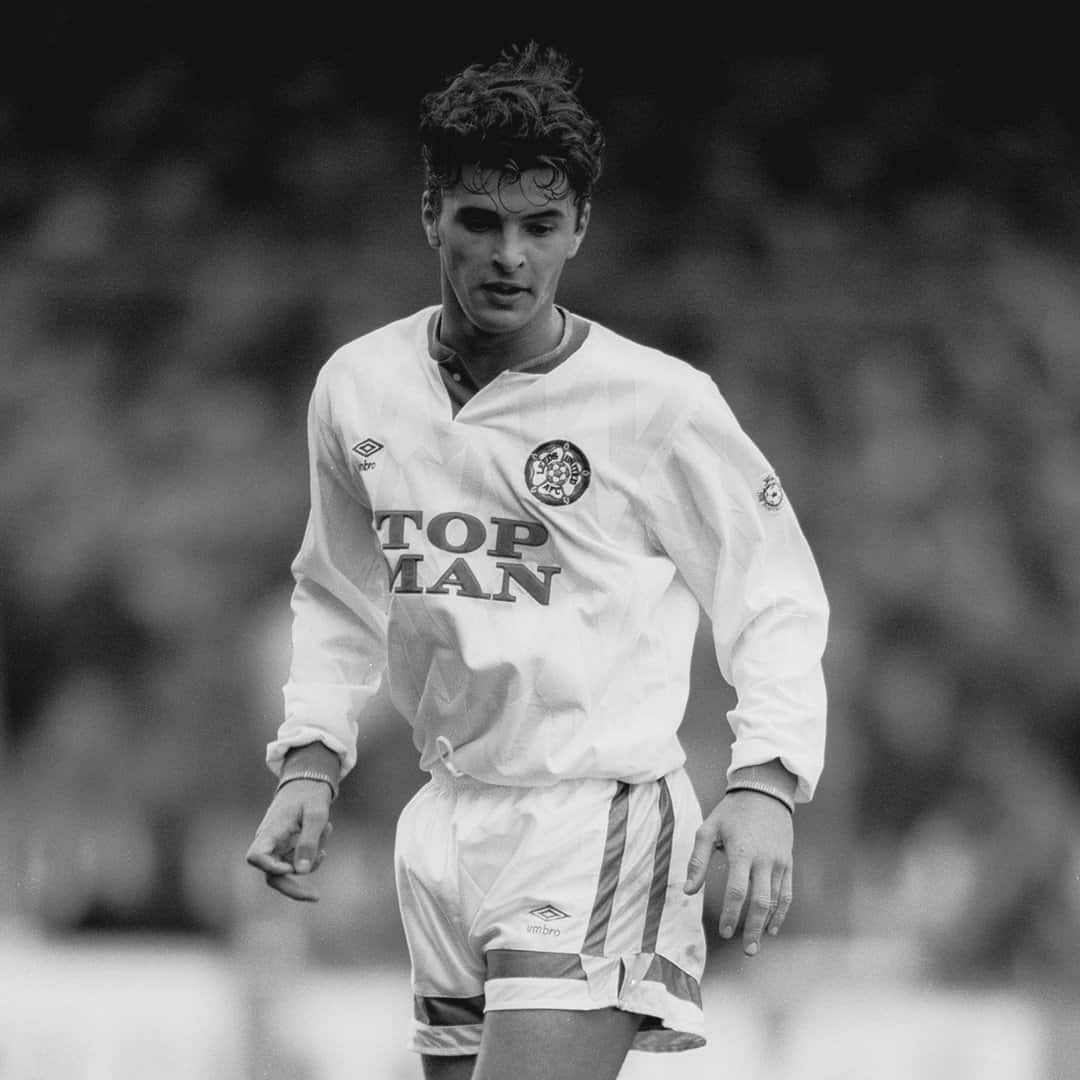

Strachan was being kept young by the midfield around him. Batty had just turned 22 and was on the verge of an England call-up. A year younger than Batty, Gary Speed was already a Wales international and had made the number 11 shirt his own at Leeds, shimmering with the confidence developed over the slog of the previous season’s promotion campaign. Meanwhile, the grace of Gary McAllister had quickly stopped Leeds fans pining for the cult hero of promotion, Vinnie Jones, who he’d replaced in central midfield. At least McAllister looked older than Strachan, even if he only turned 26 on Christmas Day, 1990, 24 hours before Leeds welcomed Chelsea to Elland Road.

Chelsea had won six on the bounce, scoring eighteen times across those games. Those victories included wins against three teams considered title contenders in Manchester United, Tottenham and Crystal Palace, setting the stage for what reporters were describing as a ‘potentially volatile’ fixture between two ‘notorious’ fanbases with plenty of shared history.

Yet despite the torrential rain over Beeston, there was plenty of Festive goodwill in the stadium. Supporters of both clubs were wearing Santa hats on the terraces as the tannoy blared Sister Sledge’s ‘We Are Family’. It was soon punctured by the Leeds fans finding their voice. ‘Heeeeee’s only a poor little cockney, BASTARD!’ As the two teams ran onto the pitch to a huge roar, Batty swiftly booted the ball he was carrying into the air like he had done countless times during Wilkinson’s tiresome set-pieces training sessions, eager to finally get the proper stuff underway.

In the opening stages, Strachan, McAllister and Speed struggled to get into the game, barely touching the ball. It didn’t matter, because the early exchanges were Batty’s domain. Leeds’ curtain-haired number 4 was a constant blur of motion, like Road Runner in a pair of Puma Kings. One second he was sliding into a tackle, the next he was anticipating a knockdown from Chelsea’s strikers and sprinting to win possession and set Leeds back on the attack, earning a free-kick as he broke upfield and getting back to his feet with his shirt already muddied.

Wherever you looked, Batty was there. Linking up with Strachan and Mel Sterland on the right wing. Racing to take a throw-in on the left touchline. Constantly in support of his fellow midfielders whenever they were in trouble, immediately winning the next tackle if they ever lost the ball. Much like Revie’s Leeds, if the opposition wanted a game of football, Strachan and co could play them off the park. If the opposition wanted a fight, Batty was more than happy to take them all on himself.

Once Batty had established the pecking order, and Leeds’ platform in the game, the rest of the midfield took over. Strachan began dancing inside off the right wing, shimmying past Chelsea players. Speed never allowed Wales teammate Gareth Hall a second to breathe at right-back, a thoroughbred of pace and power with looks that belonged in a boyband. After fifteen minutes, McAllister got his first touch of the match, feeding Speed on the left, getting the ball back and twisting past Hall twice before crossing towards Chapman at the far post. The attack came to nothing, but Leeds were starting to flex their muscles.

Slowly but surely, Leeds were building momentum. It always started with Batty winning back possession, allowing Strachan, McAllister and Speed to combine with increasingly imaginative passes. From a pinpoint Batty cross, Chapman’s diving header was saved by Dave Beasant. Carl Shutt hit the bar. Playing left-back for Chelsea, Tony Dorigo must have been dreaming of swapping a blue shirt for white, if only so it meant he no longer had the headache of trying to stop Strachan. Moments before the break, Strachan aimed a corner towards the edge of the box, where Sterland peeled off his marker and side-footed a volley into the bottom corner like it was the easiest thing in the world.

Half-time only brought a brief respite for Chelsea. Straight from the restart, they were once again being mauled by Leeds’ midfield. Speed broke down the left. Strachan followed up. The ball broke loose and McAllister was immediately snapping at Chelsea’s ankles, all legs and arms, like being closed down by an octopus. Inevitably, Batty won it back, allowing McAllister to set Speed racing down the left wing again. Speed skipped past Hall once more and won a free-kick, which Strachan swung perfectly onto the head of Chapman, who glanced it perfectly into the far corner.

Barely two minutes later, Shutt went through on goal only to be thwarted by Beasant, but as Andy Townsend aimed a pass back to his ‘keeper, Chapman raced into the penalty area, throwing himself through the air to intercept the ball and nudge it into the net for his brace. He landed on his back, arms raised in celebration, skidding across the sodden turf almost all the way into the South Stand. As Strachan and Speed congratulated the striker, offering a hand to help pick him up off the floor, Batty arrived sliding on his knees, only stopping when they banged into Chapman’s ribs with a big grin on his face, before grabbing Speed around the neck with what was meant to be a hug but more closely resembled a headlock.

Puddles were forming all over the Elland Road pitch. Lukic tried to bounce the ball in his penalty area only for it to land with a thud in the mud. Yet the worse the conditions got, the better Leeds played. A gorgeous Strachan cross almost led to Chapman’s hat-trick. McAllister spotted a pass nobody else in the stadium could even imagine to split the defence and play Shutt in on goal again. As a rainbow appeared over Elland Road, Chelsea were bogged down in their own penalty area, unable to escape the suffocating intensity of Leeds’ midfield.

Threatening a brief escape, striker Gordon Durie miscontrolled a pass, letting the ball roll under his foot and out for a throw-in as the crowd united in a huge cheer and chants of ‘eeyore, eeyore!’ McAllister left Graham Stuart on the floor with a fair tackle. The ref stopped play. Not for a free-kick, but seemingly because he felt sorry for Stuart, who stood up looking bewildered, caked in mud all over his torso and legs, down his arms, in his eyes. What was this? A football match or a battlefield? Either way, there was only one winner.

For just one moment, Leeds relented. A misplaced Sterland pass finally let Chelsea out of their own half and drew Chris Fairclough out of position. Durie crossed and Kerry Dixon headed into the bottom corner. Finally the away fans had something to cheer about, only to be swiftly shut up by Chapman responding to some stick by holding up two fingers to remind them of how many he’d scored.

In the quagmire of the middle of the pitch, Batty robbed Townsend and dribbled away coolly to lay the ball off to Sterland. Townsend replied with a sly trip on Batty after he’d passed, who bounced back to his feet and turned to find the perpetrator, snarling at him with a dismissive flick of the head. “Fuck off!” As Townsend quickly ran off to get back into position, puffing out his cheeks, Batty’s face broke into another grin.

Leeds were never going to let Chelsea have the last say. For the thousandth time of the afternoon, Batty won the ball. Chapman played a one-two with McAllister, before hoofing a cross into the air towards the edge of the box, where McAllister was now stationed. He brought it down with his chest and, as the other 21 players on the pitch moved around him, briefly stood still, waiting to tee up sub Mike Whitlow, who unleashed a stunner into the top corner.

Leeds were up to fourth and had gifted their fans the perfect Christmas. Having been pilloried in the press for insisting football was about winning rather than entertaining, Wilkinson asked reporters after his side’s biggest win of the season, “But was it good entertainment?” The Yorkshire Post’s Barry Foster approved; Leeds ‘walked on water’ in the rain, he wrote the following day.

When Wilkinson had taken over at Leeds two years earlier, one of his first acts was to take down photos of the Revie years from the walls of Elland Road until United had a team to do them justice, and now he and his players were getting the ultimate seal of approval from one of Revie’s greats. Johnny Giles relished “the brash new boys on the block” once again threatening the “establishment” of England’s elite. “Leeds are probably a couple players short of challenging Liverpool but of all the up-and-coming teams they are easily the most exciting,” Giles said. “They play with skill and at great pace. They can trouble anyone.” And best of all, they were just getting started. ⬢

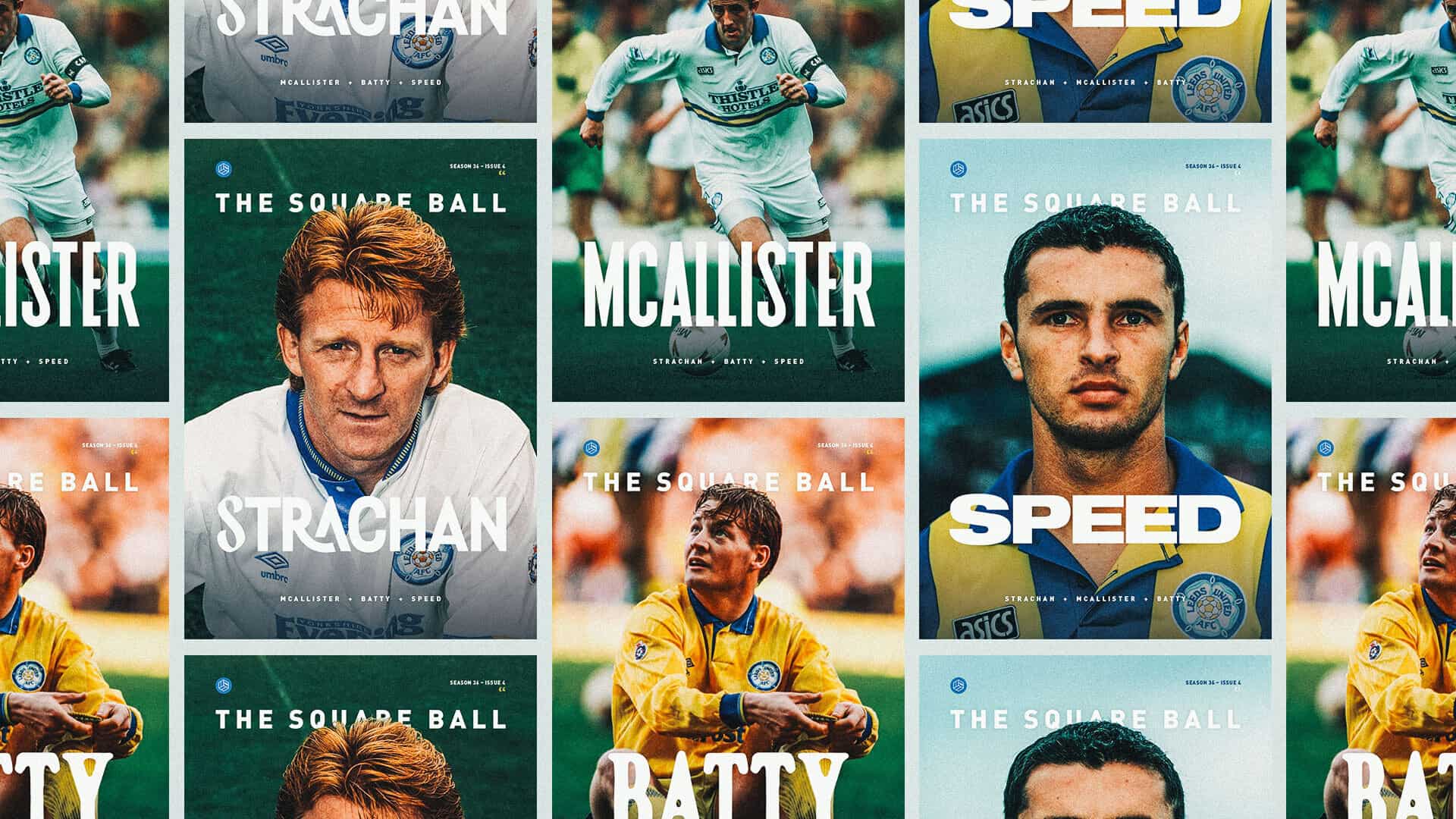

This article is free to read from issue four of The Square Ball magazine, a mini-special celebrating our title-winning midfield of Gordon Strachan, Gary McAllister, David Batty and Gary Speed. Four heroes, four covers, and four free stickers with every pre-order — all for just four quid.

£19.99

£3.00

£35.00