Swimming against the tide

The Great Wearside Piss Flood of 2023

Having survived the toilets at Elland Road, it sounded more like a challenge than a warning when a friend returned to his seat at the Stadium of Light shortly before the second half began and told me, “It’s flooded with piss.” Nature was calling me, in more ways than one. It’s not every day you get to witness the phenomenon of a piss flood. And, well, I needed a piss too.

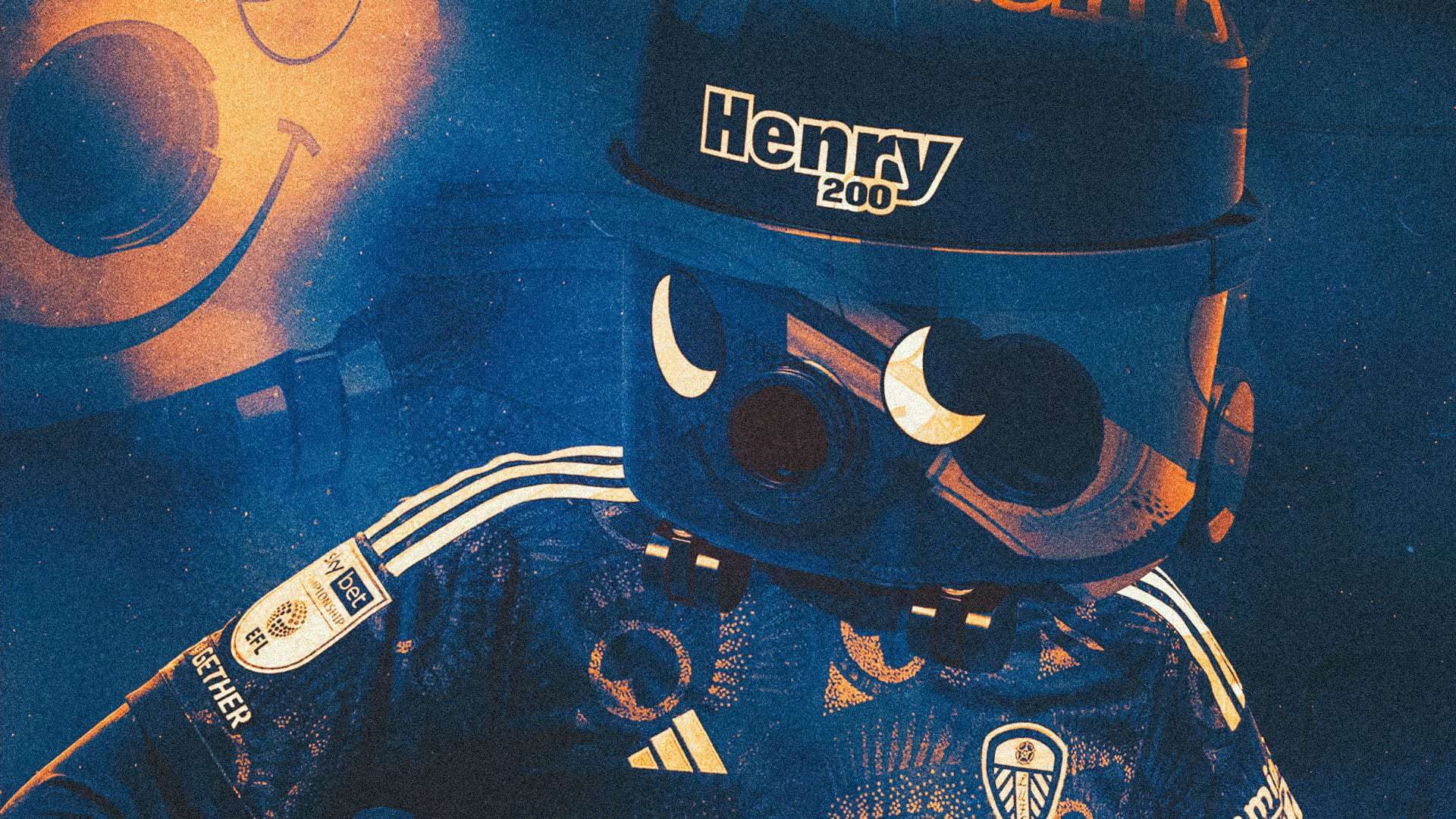

By the time I walked down to the toilets, the flood had subsided into more of a small lagoon. A member of stadium staff was solemnly tackling the problem with a knackered old Henry Hoover. Thankfully the path to the urinals on the left was by now mostly above sea level, recreating a popular North East scene of people cautiously trying to jump over puddles that was briefly a viral live stream. But supporters wanting the privacy of a cubical to the right were donning a snorkel and flippers in fear of being lost to the tides of pish, their souls doomed for an eternity in a yellow Atlantis. My heart went out to those supporters. Even Henry had stopped smiling.

The Stadium of Light felt like one big trap for Leeds on Tuesday night. On the way into the ground, stewards robbed supporters of coins and vapes. While the fans in the away end were trying to keep dry and not get submerged, Sunderland were better and more organised than a team without a manager should be, and Leeds seemed spooked by their own rare lack of urgency and imagination.

For most of this season, each part of Leeds’ team has been able to play with the confidence that everyone else around them is also doing their job — a solid defence has known they’ve been protected by a midfield controlling the tempo, and the midfield has known if they give the ball to the attack, something fun has usually happened. But it seemed to dawn on the players that the usual plan wasn’t working, or at least Sunderland’s concentration wasn’t wavering, leaving eleven misfiring individuals trying to make things work on their own.

To their credit, each player still showed moments of skill, graft, and promise, but unlike previous weeks they all had moments that drew my gaze to the dugout, wondering how Daniel Farke could change things. Joe Rodon and Pascal Struijk couldn’t work out between them who should challenge for a header. Glen Kamara and Ethan Ampadu gave the ball away sloppily, trying to force forward passes into the mass of bodies that Leeds’ wingers only added to by cutting inside. Djed Spence and Crysencio Summerville kept bumping into each other, making the same runs off the left wing. Georginio Rutter looked like he was playing on his own.

Stuck in their own swamp of Sunderland defenders and with no better ideas, Leeds kept passing the ball back to Rodon and Struijk, who were the last people that needed it. They looked thoroughly fed up with having so much possession. Shouldn’t this be someone else’s job? Rodon was so fried by trying to find some space to put the ball that he passed it straight out for a throw-in twice in injury time. Spence summed the night up by slowly ambling off the pitch when he was subbed, taking all the time in the world even though Leeds were losing and needed a goal while the away end threatened to simmer.

Still, it’s fine. It’s football. This is what sometimes happens. Sometimes it just doesn’t work. Unlike previous seasons, Leeds at least have evidence that it works more often than it doesn’t. Leeds went to Sunderland unbeaten in seven games, having won ten of their last thirteen. Even after losing, Leeds have the same number of points as last season’s champions Burnley at the same stage of the campaign.

If the toilets were anything to go by, maybe it was a night for everyone to get it out of their system all at once. There was plenty of knicker wetting on social media after the result, but if Leeds keep doing what they’re doing for the rest of the season, however it ends, nobody will remember The Great Wearside Piss Flood of 2023. ⬢