Limited Time Discount! Shop NOW!

A crumbling stadium in south Leeds fits perfectly with the aesthetic of rugby league, yet the reaction to the news that Elland Road will host next year’s Magic Weekend — when all twelve Super League clubs will play a round of fixtures across two days — was entirely predictable, even if it wasn’t necessarily unfair.

‘Genuinely think it would have been better to kill off Magic Weekend than have it at Elland Road,’ wrote The Guardian’s Aaron Bower on Twitter. ‘Fans should boycott,’ read one reply, missing the point that part of the reason the event will be held — potentially for the last time — at Elland Road is because previous years have only ever half-filled stadiums in Newcastle, Cardiff, and Liverpool. But Leeds is as popular among rugby league circles as it is among football supporters. Sure, the facilities are outdated and the queues outside Graveleys might get a bit long, but the prevailing argument from fans of rival clubs boiled down to: ‘Of all places, we don’t want to go to bloody Leeds.’

Moaning about playing rugby league at Elland Road is part of the sport’s heritage. Since 1895, rugby league has been in a permanent existential crisis, constantly yearning for evolution while proving the old adage that the more things change the more they stay the same.

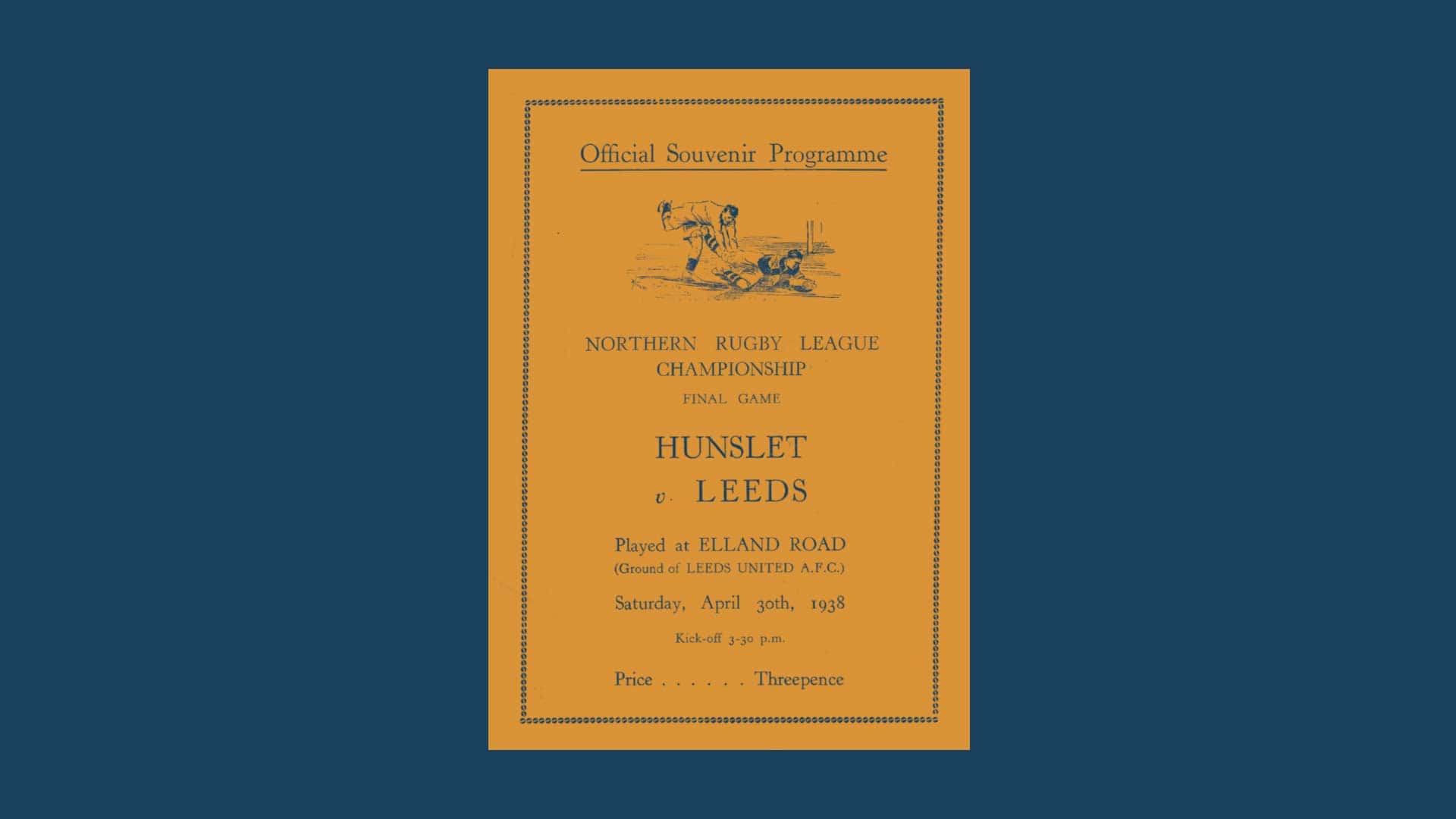

In 1938, Leeds and Hunslet lobbied the Northern Rugby League Committee for their championship final to be switched from Wakefield’s Belle Vue to Elland Road. The rationale was sound — two clubs from the same city, meeting at a venue easier for their supporters to attend, with a much larger capacity to attract a crowd more fitting of such an occasion. The committee originally rejected their proposal, made before the semi-finals were played, but agreed to meet once again on the night of Leeds’ play-off against Swinton at Headingley. After Leeds were victorious, a small crowd gathered outside the Headingley pavilion awaiting the news they were hoping for: the final was to be switched to Elland Road, with Wakefield receiving £300 compensation, and both Leeds and Hunslet agreeing to take £600 each of the gate receipts, rather than the third they would usually receive, allowing the Committee to have the rest, estimated to be around £2,000.

It still wasn’t good enough for some. A letter to the Yorkshire Evening Post suggested, ‘A boycott of the game should ensue not as a gesture of hostility to either team but as a protest against the spineless and cowering Rugby League authority — rules and the game don’t count when the purse is dangled. Yours etc, DISGUSTED, Ossett.’ Another letter complained of the ‘partisanship’ and ‘rabid element’ of Leeds’ support that ‘approaches fanaticism’. The crime of the fans was occasionally booing refereeing decisions and opposition goalkickers. Discovering the letter almost a century later, I’ve never felt so proud.

The sentiment of those proposing a boycott clearly wasn’t shared. A crowd of almost 55,000 attended the final, setting a new record for British rugby league. Many more were locked out, with those trying to climb the roof of the stadium chased away by police officers. Others opted for the view from the roof of the Old Peacock, and could climb down at full-time for an extra couple of pints after pubs around Beeston were granted an extension of their licence by an extra half an hour to 5.30pm.

Rugby posts had to be borrowed from Hunslet’s Parkside ground and erected at Elland Road on the day of the match ‘after being given a coat of lime’. Hunslet won the toss and got to use the home changing rooms. ‘By the middle of the afternoon Elland Road looked as though an Association ball had never been kicked on it.’ Leeds had reached the final on four previous occasions, but never won. Their team contained draughtsmen, PE teachers, cabinet makers, blacksmiths, joiners and a landlord. Before the game Leeds’ returning captain, the Australian half-back Vic ‘The Human bullet’ Hey, promised, “We shall win. We have no doubt about it.” True to form, they lost, 8-2. Celebrating Hunslet fans were asked not to invade the field; ground staff were working on a quick turnaround so the pitch would be ready to host Leeds United Reserves’ Central League fixture with Everton that same evening.

During a never-ending period of tinkering with the league structure, Elland Road didn’t host another play-off final for almost fifty years. But when St Helens and Hull KR met in the decider in 1985, it was apparent the sport was changing, at least on the pitch, if not in the erratic administration off it. The programme for Hunslet’s win over Leeds had featured a page detailing the height and weight of each player — all but two players were under six feet and fourteen stone. When St Helens came to Elland Road, their side contained all 6ft2in and 16st of the Australian icon Mal Meninga. Most frighteningly, Meninga wasn’t even a trundling forward. He was a strike centre, a thoroughbred of a rugby league player, combining pace, power, and ‘real mule-kick of a fend-off’.

Meninga can legitimately claim to be one of the sport’s greatest. A record-breaking player and coach, he was named one of the game’s ‘Immortals’ in 2018. He also holds the unofficial record for the shortest political career in history. In 2001, he spent six weeks preparing for a radio interview announcing his candidacy as an independent for the seat of Molonglo in the general election. None of his team had the foresight to prepare him for the interviewer’s opening question: ‘Why should people vote for him?’ “I’m just a person out there making sure,” Meninga began before nervously laughing and holding his hands up. “…I’m buggered. Sorry.” He stood up, walked out of the studio, and resigned — 55 seconds after the interview started.

Whereas Hunslet’s low-scoring victory over Leeds failed to match the spectacle of the record crowd, Meninga’s brilliance at Elland Road deserved a bigger audience than the 15,000 in attendance. Hull KR were favourites after finishing top of the league, but St Helens triumphed 36-16. Looking like an athlete from a different sport, when Meninga wasn’t skittling Hull KR players in both defence and attack, he was scoring twice after intercepting passes, out-sprinting the opposition the length of the field for his second, after which a supporter in the Kop celebrated by holding up a banner that read: ‘Saint Mal The Wizard Of Aus!’

Hull KR were coached by their own icon, Roger Millward, a former Great Britain hero who has a road linking east and west Hull named in his honour. Millward later became more familiar with south Leeds by quietly pottering around as the caretaker of my old high school. Some KR fans gathered outside the changing rooms at Elland Road to sing in salute of their team, only for a ‘missile’ to be thrown at the crowd by Saints supporters, shattering a window and showering their dejected players with broken glass while they were in the team bath. On the same day, Leeds United fans were rioting at Birmingham, or as the Birmingham Mail put it, ‘Leeds louts showed again the bloodied flag of anarchy.’

If Meninga was playing like the future of rugby league, it was a future that belonged to Leeds. Thanks to their success in Super League, Leeds Rhinos regularly called Elland Road their home in World Club Challenge finals against the winners of the southern hemisphere’s NRL competition.

After ending their 32-year wait for a championship in 2004, Leeds faced Canterbury Bulldogs the following February as a record crowd for the fixture witnessed an electric Rhinos side winning 39-32. Boyhood Leeds United fan Danny McGuire broke the game open with a searing individual try, dancing around defenders from his own half and into the corner to score what he later told me was his impression of Rod Wallace’s solo goal against Tottenham, “when he took them all on and banged it into the top corner — for me to get the chance to play there in a massive game, in a packed house as well, was really special. Throughout my career, that’s probably one of the best memories.”

The Rhinos were back at Elland Road in 2008, facing a Melbourne Storm team that was literally too good to be true. They were in the middle of four consecutive NRL grand final appearances, but were later stripped of the two titles they won having been found guilty of systematic breaches of the salary cap. One newspaper dubbed the episode ‘the biggest scandal in Australian sports history’.

Played in a storm of Forrest Gump proportions, a swirling wind meant the pitch and stands were drenched by rain that came from every direction — vertically, diagonally, horizontally, sometimes it even seemed to come straight up from underneath the turf. Melbourne went ahead in the first half, and Leeds lost Danny McGuire to injury, but the match turned when Storm winger Steve Turner ran the ball into Jamie Jones-Buchanan’s shoulder and was flattened in front of the Kop, Jones-Buchanan cracking him once more to make sure Melbourne knew whose home they were playing in. Leeds scored a few minutes later to take a lead they didn’t relent as they won 11-4 to become world champions again.

A few years ago, I interviewed Jones-Buchanan at Headingley and asked him about that tackle. He grinned, and unzipped his jacket to reveal he was wearing a Leeds United jumper. “If I’d have done that now I’d probably get banned for three or four games,” he said. “It was one of my favourite parts of my career, if not favourite. It just needed something to lift the game. Growing up in Leeds I always had this recurring dream of playing for Leeds Rhinos and Leeds United. I remember after that shot the Revie Stand celebrated as if somebody had scored a goal. Everybody just lifted. We look back on that and we beat the mighty Melbourne Storm. We bashed them, mate! And on, for me, an amazing stage.”

Rugby league has spent over a century wrestling with its own heritage, asking questions of its identity that nobody has been able to answer. I’m starting to wonder whether we’re asking the wrong questions. Rather than worry about why rugby league isn’t a bigger sport, maybe it’s worth contemplating why it has survived since 1895.

When Hunslet beat Leeds at Elland Road in 1938, a reporter from the Leeds Mercury with no interest in the sport attended the match and was stirred by the occasion. ‘Conscience whispered that I had no right to watch the rugby league final,’ they wrote. ‘Conscience said I ought to be in my garden howking up daisies on the lawn. But when I reached the football ground and got my breath after the jostling in the streets, the voice of the blood — Yorkshire sporting blood — became clamorous. Towards the end the spirit of the fifty thousand was gladiatorial. There was many a spell when excitement gripped one like a danger.’

It doesn’t sound too bad, does it? It certainly beats playing at Wakefield. Or even worse, Wigan. ⬢

£2.50

Copyright © The Square Ball Media Limited All Rights Reserved

WordPress Development By Clio Websites